The dinosaurs that have been excavated from the Alberta badlands for over a century are famous the world over. They’re featured in books, TV shows, movies, and photos in the Flickr and Facebook accounts of thousands of tourists. Tourists flock to the valley year after year to get a glimpse of the amazing fossil record that is here.

However, whether you are in Drumheller, Ottawa, New York, or London, England, you can still find dinosaurs from the Alberta Badlands.

Sometime before 1871, a Jesuit priest, Jean-Baptiste L’Heureux, was living with Native Americans in southern Alberta. It was during that time that L’Heureux was shown bones of “the grandfather of the buffalo”, or what was soon to be identified as the fossilized bones of dinosaurs.

George Mercer Dawson, son of palaeontologist Sir William Dawson, first officially reported dinosaur remains in Alberta in 1874 while working for the North America Boundary survey. The remains Dawson collected found their way to the famous American palaeontolgist Edward Drinker Cope.

Colleagues of Dawson working in Alberta began to find more material. Richard McConnell found remains at Scabby Butte in 1882 and Thomas Weston found dinosaurs in 1883.

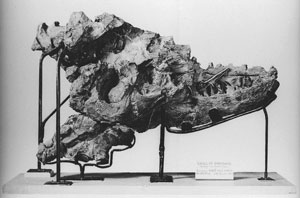

The most famous discovery, and the one that has had the greatest lasting impact, is that of a young geologist looking for coal seams in the Drumheller area in 1884. Joseph Burr Tyrrell, the namesake of the renowned museum, came across the skull of what would be named Albertosaurus.

After Tyrrell’s discovery, more palaeontologists flocked to the Red Deer River Valley.

In 1889, Weston returned to the area and floated down the Red Deer River and collected a second Albertosaurus skull.

Lawrence Lambe from the National Museum of Canada collected fossils from the Red Deer River in 1897 and 1901. Benjamin Bensley, a zoology professor from the University of Toronto, was inspired by Lambe’s finds and came to the area as well in 1908.

In 1910 a rancher from Drumheller, John Wagner, was visiting the American Museum of Natural History in New York in 1909 and told staff that he had the same bones on his property. The following year Barnum Brown briefly visited the area after his work in Montana was finished and planned an expedition to the Red Deer River in the summer of 1911.

Brown spent the summer of 1911 floating down the river in a wooden scow and would stop periodically to collect fossils. One of the most significant finds during that trip was the Albertosaurus bonebed in Dry Island Buffalo Jump Provincial Park. The site has been the subject of considerable research effort by Royal Tyrrell Museum and University of Alberta crews between 1998 and 2011. In 1912 to 1915 a local homesteader, William Cutler, joined Brown’s crew.

The Geological Survey Canada upon hearing of Brown’s finds decided to hire their own team in 1912 to collect fossils from the badlands. Charles Sternberg from Kansas brought two of his son, Charlie and Levi, to compete with Brown. The two crews were generally on good terms, but stayed out of each others way for the most part. Brown continued to work in the Alberta badlands until 1915 and the Sternberg’s continued until 1961.

The early fossil pioneers of the Red Deer River made phenomenal discoveries, but those fossils are no longer here. During these early years the collectors who came to the area were working for the major museums and universities in eastern North America and Britain.

The skull that Tyrrell found was taken east to Ottawa. The hundreds of specimens that Brown collected were shipped to The American Museum of Natural History in New York. The Sternberg’s were each hired by a number of institutions and their finds were sent to the Royal Ontario Museum, Canadian Museum of Nature, and to the Natural History Museum in London.

Alberta dinosaurs could also be entombed in the murky depths on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. Charles and Levi Sternberg worked freelance during the summer of 1916 because the Geological Survey of Canada had no funding due to the war. Charles and Levi came to Alberta to sell dinosaur skeletons to the Natural History Museum in London. One of the two shipments of fossils came under attack from German ships and was sunk.

Apart from two excursions in 1920 and 1921 headed by George Sternberg on behalf of the University of Alberta, the fossils collected in Alberta did not stay here. It wasn’t until the late 1950s and early 1960s that Albertan institutions were the dominant collectors of fossils from the area.

Fossils collected in the badlands continue to shed new light on dinosaurs, and even those fossils housed in other institutions around the world giving new insights. For example, a new horned dinosaur, named Spinops sternbergorum, from Alberta was found in the collections room of the Natural History Museum in London. The specimen had been collected in 1916 by Charles and Levi Sternberg and shipped overseas (in the shipment that wasn’t sunk). There the fossil sat on the shelf for 90 years before being named a new species.