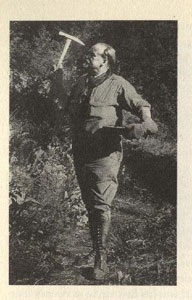

Throughout the centennial year of coal mining in Drumheller, there has been a familiar face at many of the events. He cuts an unmistakable figure - often in a bowler hat, a buffalo skin jacket and an upturned moustache.

This blast from the past is the Atlas Coal Mine’s Jay Russell, who has been portraying J.F. Moodie, the founder of the Rosedale Mine. This is not just simple play-acting; Moodie left his mark on the valley in myriad ways, held up as an innovator, reviled by labour movements, and forging his legacy along the way. Russell has embodied the legendary mine owner.

“We (Drumheller) have a lot of real interesting characters, so we were looking for someone who was not only colourful, but flamboyant, perhaps a little controversial, and was integral to the development of the Drumheller Valley. Mr. Moodie certainly fits that,” said Russell.

While his stint in the valley was only about a decade, he was held up as a model example in the creation of his modern mine. He was also centre stage in one of the most bitter labour battles in the valley, even hiring spies and funding “special constables” to take care of agitators. He was an original.

Born in Chesterville Ontario, he came west in 1901. In 1911, according to J. Frank Moodie: The Man and the Mine, written by his granddaughter Catherine Munn Smith, he had a vision to open and operate a model mine, with decent living conditions for miners in an adjacent village. To this end began the Rosedale Mine.

The Moodie Mine “was safer and more efficient, had better sanitary conditions, and paid higher than union wages. In addition, the adjacent company-owned townsite had educational and recreational facilities that surpassed every other mine site in the province,” said his biographer.

“This was his vision,” said Russell.

“He was going to make a state of the art coal mine in which the management recognized the dignity of both the work and the worker,” said Russell. “Back then… things were pretty rough and tough, there were nicknames like ‘Hell’s Hole’ and ‘Devil’s Row’, and I don’t know for sure, but I suspect he saw these places and saw how rough they looked and how poor these conditions were…I think he took pity on the working guy.”

While his model showed considerable respect for miners, he often was not all that liked. It may have been his ostentatious lifestyle, or maybe what would be defined today as ‘micro-management’ style. He was not a fan of organized labour and it was not a fan of him. The irony is that both were probably working toward the same goals.

“Even though he was trying to achieve the same things that unions were trying to achieve, I think he wanted to do it in his own way,” said Russell.

Labour actions in 1918 and 1919 became brutal battles. When agitators entered his property, he would make sure they were not welcome. One time one was reportedly bound and he threatened one with a gun. Moodie was tried for the incident, found guilty and fined.

He lost trust with his workers and at one point hired a detective from the Pinkerton Detective Agency in Seattle to work alongside the miners and spy.

Russell said Moodie played a big role in crushing the strike of 1919.

“Moodie was a proponent of hiring what they called ‘special constables,’ strikebreakers. These ‘special constables’ were provided with government granted crowbars and brass knuckles and all the alcohol they could drink, even though it was prohibition, and they would go around and if a miner was on their own, he was risking his life.”

He adds that there were even machine guns guarding the mine from agitators.

The strike of 1919 ended when One Big Union was driven out of the valley.

Russell suspects the labour issues are what made Moodie exit the coal business and the valley.

“I think he suspected the miners were not grateful to him for providing all this stuff, and I suspect the miners thought of him as overly paternalistic,” said Russell. “He probably left because it wasn’t the utopian ideal he hoped.”

Moodie went on to get into the oil business, and even a failed political venture running for a Calgary seat in the 1940 provincial election. He was injured in 1938 in a car crash and never quite recovered, and died in 1943 at 64.

His life has been written about by a number of historians but his story has received a revival through Russell’s characterization. He is not afraid to share stories. He is featured in promotional material for the centennial and even a fun back-to-the-future Youtube video.

“He was quite a guy,” chuckles Russell.